- Gepost von: Maarten Van Duren Laurens Koppenol Olaf De Leeuw

- Datum: 23 Oct, 2020

- Kategorie: Data Engineering , Data Science

Introduction

Barry is a data scientist working for a small data science and engineer consulting company based in Utrecht. So far in his career, he has developed tons of state-of-the-art machine learning products. Barry is used to working with large data dumps on his local machine.

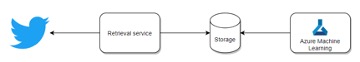

Barry is on holiday and, as borders are closed, decides to pick up a personal challenge; analysis of large quantities of Twitter messages to predict the current mood of tweeters. Barry’s girlfriend is a great data engineer, who is charged with the responsibility of incoming data. For the first time in his career, Barry is handed the great opportunity to work in the cloud. His girlfriend sets up the following scenario in Azure:

Barry and his girlfriend decide to use a well-known concept from software engineering, CI/CD, in their project architecture. Because Barry is going to build a Machine Learning model, he will face some challenges while working according this concept.

In this article we will talk about Continuous Integration / Continuous Deployment for Machine Learning projects, or CD4ML. An important aspect of CD4ML is versioning and by that we mean both model versioning, and data versioning.

Model versioning

During a data science project, data scientists and machine learning engineers like Barry tend to experiment and train lots of models. Which is a good thing because, step by step, Barry produces better and better models. But things get complicated when he moves towards production or the model eventually has to travel through the deployment pipeline for a release. Questions arise like: which model is in this release? What were the model’s performance metrics? On which data set has that model been trained? What were the model’s hyperparameters? How does the next model compare to the previous model? All common questions that you also might have heard as a developer from your Product Owner, Management or end users.

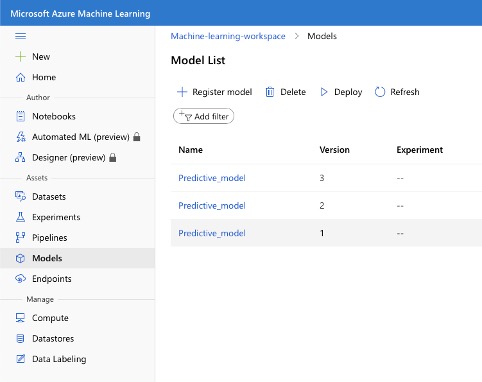

All of these problems and questions are addressed with model versioning. Model versioning is a combination of technical tools and a way of working. Envision it as a repository or inventory of models. With each model, all the relevant properties are logged. Barry is able to compare any model to any other model by their performance metrics, retrieve any model and deploy it, backtrack the model to the experiment and the data set it was trained on, revert the deployment of a model, etcetera.

Another benefit is that model versioning enables the model training and model deployment to be separated. Data scientists excel in training models and improving upon them. However, they generally do not excel in building technical infrastructure and solutions to deploy and serve models. Model versioning allows data scientists like Barry to simply put a model in the repository and trigger a deployment. A data engineer can develop the technical infrastructure and solution to deploy and serve the model. All the data engineer needs to do is pick up the model from the repository. Splitting these tasks with model versioning in between them allows both Barry the data scientist and the other experts to focus on the things in which they excel.

An excellent tool for model versioning is MLFlow. It can be used as a standalone product, but it can also be integrated into Azure Machine Learning and Azure Databricks. In all setups, MLFLow offers the functionality that Barry needs. Since his project runs on Azure, there are additional benefits of using MLFLow in Azure Machine Learning or Azure Databricks. Mainly because of their excellent integration, reducing work, reduced complexity, and less risk for Barry.

At ProRail, the organization responsible for managing the railroad network in The Netherlands, the image recognition team uses MLFlow and AzureML much like Barry. Trained models are put in a model repository which brings all the benefits described above. With those benefits, ProRail saves a lot of time and resources that comes with managing predictive models and instead spend that time and those resources on more valuable things. One of those things is a custom integration with Azure Databricks, enabling data scientists to monitor model training more closely. This enabled them to develop even better models and have more control over fine tuning the models to the specific needs of the use case. Ultimately, this results in data scientists spending more time and energy into developing and enhancing the model itself, resulting in more value to ProRail in less time.

Data versioning

Let’s see how Azure might help Barry. Barry starts exploring the Twitter data using Azure Notebooks. As the retrieval service was only just spun up, Barry is slightly disappointed with the quantity of data available in Blob storage. As the week progresses, Barry develops his first model, predicting Twitter’s mood based on the topics of the day before. Just before the weekend, Barry ran his model and got his first performance measure. Happy with the result, Barry sets his mind to activities to something even more fun than data science.

On Monday morning, Barry has a coffee and starts refreshing his memory. Reminding himself of his great success on Friday, he struggles through his Azure Notebook and manages to rerun the exact same code he ran last Friday. Astonishingly for Barry, the Notebook result is overwritten by a totally different model performance, despite not changing any code or model variables!

Oh no! What has happened?

As you might have guessed, the model is trained and evaluated on a different set of data, namely a larger corpus of Tweets than the week before. Let’s discuss how we can prevent Barry from getting frustrated in the next weekend by introducing more reproducibility for models, based on data versioning.

The example above demonstrates how a changing data source, which is a very common occurrence, can lead to surprises. A common practice to avoid this is to make sure a data set cannot change, for example, by copying a data set to the environment where the data scientist is working. But this will lead to problems; for instance, when other data scientists have their own models with another copied data set or when you want to deploy your model to production. In that case, you end up with a static data set in your production environment and upgrading your model with the latest data becomes more complex. A better approach is to leave the data where it is and assign versions to various states of a dataset, just like we do with code or with models, as described above.

We will focus on how to add data files to file storage as described in Barry’s example, but other types of version changes of a data set could be the insertion or the updating of a row in a database.

The main reasons for data versioning are to increase reproducibility and to reduce various kinds of unexpected behavior.

Datasets, Experiments, Runs, and Logs

Azure Machine Learning can connect to a data set, for example a specific path on a Blob storage. When a file is added to this path, it is automatically available to the data scientist working with Azure Machine Learning.

When Barry executes a cloud training job, he actually starts an Experiment, in which various Runs of a model can be executed. He could, for example, start an Experiment called “Twitter classification” and execute multiple training jobs with different model settings (hyper parameters) in parallel, as different Runs. Each Run results in a prediction of the Twitter Mood with its performance measures.

During such a Run, Barry sees the output of his training job via the Azure Machine Learning Portal. This logging is not to be confused with meta data we can assign to a Run during training, which are called Logs. Logs are important as well to know which hyperparameters were used such as the number of epochs and the learning rate. However, here Barry is looking at the output logging of a Run. This could be the performance of a model after it is trained and evaluated, the model parameters before the training has started, but also the training loss during training of a model allowing for early termination of bad models.

Besides logging and Logs, it is also possible to write files to Azure Machine Learning which are assigned to the Run. This could be the model itself (which also has a designated location, the model repository).

Freezing a data set within an Experiment

The following steps can be easily implemented in any model training script. Because logging file names will quickly exhaust the maximum log size several additional steps are needed to create files, and log references to them.

- Add a check in the model training code whether it is the first Run in an Experiment

- If first Run:

- Get all files available in the available Datasets

- For all Datasets write a file to Azure Machine Learning containing all available files

- Log a table which links the Dataset identifiers to the path to the files

- If later Run:

- Retrieve the Log from the first Run containing the Datasets to file list mapping

- Retrieve the file lists

- Select only the files which were used in Run 1

This algorithm ensures that subsequent runs always use the data files of the first run so we can enjoy reproducible and comparable results!

Data versioning of files in Azure Machine Learning

Always keep in mind to keep your data source connections safe and maintainable, whether you are using managed connections such as Datasets and Datastores or other types of connections. Despite being a highly managed service, Azure Machine Learning allows customization of the resources used underneath, opening up several networking and authorization options. This might even allow you to go as far as meeting your corporate security regulations, which are not often aimed at (public) cloud environments.

Want to know more about the security aspect of Azure Machine Learning? Stay tuned for the next episodes of CD4ML!

CI/CD & Model building

In this section we’ll discuss the well-known concept amongst developers of CI/CD (Continuous Integration, Continuous Deployment). The main purpose behind this idea is to bring your code -, your application to your end users faster: Instead of packaging application features in huge release packages, every feature should be able to be deployed directly after it has been built. That way you have less (error prone) code changes, you get fast feedback about the success of your feature, and of course have a fast Return of Investment (ROI). It provides reliable software by covering automation, testing, and quality checks. The concept is widely used in all kinds of software development teams.

With the rise of Machine Learning new challenges have popped up. As a development team, Barry and his girlfriend are not only dealing with changes in code, but Barry’s ML models can change as well and data used in thosemodels (see above). Data scientists like Barry are continuously working on better models, trying to get that accuracy a bit higher for instance. Barry might experiment with hyperparameters or add new features. Once he discovered that new features are needed the input data might change too.

Besides that, it is always a good idea to retrain your model with new data every now and then. Like in Barry’s project which predicts the current mood on Twitter. What if there is a new trending topic lasting for days or weeks with words his model has never seen before? For instance, words like “Corona” or “Covid-19”. These words may have a big influence on the mood. His model may suddenly perform much worse because of the numerous tweets containing all the new words. So Barry should retrain his model with the new data to keep up.

There is another challenge next to the one we just described. In traditional software development, teams probably only have to deal with a number of software engineers and maybe a couple of data engineers. In ML teams, the diversity of expertise is often much bigger. The team may consist of software engineers, data engineers, data preparation experts, data scientists, etc., all with their own expertise. Take Barry, a data scientist, working together with a data engineer. In practice, data scientists tend to work locally in their own notebook developing a great model. This model has never seen the data and code in production. So here is the next challenge. With bigger cross-functional teams, continuous integration is even more important. Like Barry, you want to keep all the developed models properly versioned in one place.

As mentioned in the last paragraph, data scientists tend to work alone in their notebooks. So does Barry. He develops his models and runs several experiments to find out which features and hyperparameter settings lead to the best performance. The developed models are all stored in his Model repository. Within Azure Machine Learning he is able to compare different versions of the developed models. At this moment, Barry decides manually when he thinks a model is ready to upgrade.

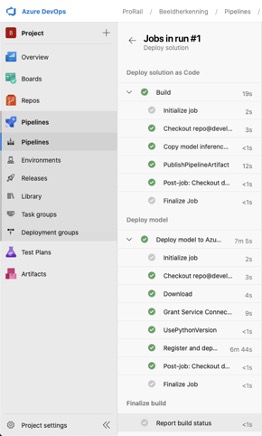

The deployment of the developed models must be automated: Without automated deployment and testing, continuous deployment of small changes would be error prone, very time consuming and thus impossible. What Barry needs is an engineer, maybe his girlfriend, to build a pipeline with an automated check if the performance of his new model is good enough. He can build logic that compares these metrics against the model in production. In case the new model performance is worse, the deployment fails. But if the model turns out to perform better, the old model will be replaced by his new model.

At ProRail, trained models are stored in a model repository. Next thing the image recognition team did was build a custom integration with Azure Databricks, enabling data scientists to deploy models from Databricks with a single push of a button. That deployment pipeline runs in Azure DevOps. There, the model itself and accompanying software are put through some final automated tests and checks to make sure the final machine learning application is guaranteed to work as expected and the deployment succeeds. Ultimately, this results in more stable and reliable applications, that can be deployed in way less time and effort. Which in turn enables updates to be developed and deployed much faster and thus delivering value to the business much faster.

Conclusion

A few weeks into the project, Barry already reached his goal. He put his trained models in a model repository, versioned his training data, and used CI/CD pipelines to deploy his models and application. That enabled him to have more fine-grained control over the model developing process, the ability to reproduce, and deploy tested and stable machine learning applications automatically. Ultimately saving time and resources, while delivering a more valuable result at the same time.