- Gepost von: Mischa Ungermann Philip Dießner

- Datum: 18 Feb, 2022

- Kategorie: Data Engineering , Data Science

Introduction

We started our journey to become Data Scientists as PhD Students figuring out by ourselves what to do when confronted with a huge dump of data. Just like almost anyone in the community, we were stepping into the data world together with Jupyter. It’s a fantastic and popular tool and nothing beats its convenience in exploring data engineering and data science relevant tasks.

But unfortunately, Jupyter alone did not allow us to be productive Data Scientists when we switched into a professional context. The key question was not anymore “What is the best way to arrive at a high-performing machine learning (ML) model?” but “How can we add value with our work?”. And of course the answer is: it depends. This question needs to be asked and answered for every new project again! And in this blog post we provide some of the guidelines that we use for orientation every time that we have to give this answer.

In the real world models need to be applied “reproducible” and “structured”, and there are so many steps involved in a ML project that even during a Kaggle competition it is advised to have a tool chain in place that extends (or completely replaces) a set of Jupyter notebooks. But before we jump straight into a tool discussion (spoiler alert: there are many - and we are always excited to discuss them, but have to refrain ourselves here), we want to take a step back and consider a machine learning “lifecycle” in the context of real world applications. Especially: which perspectives on this topic do already exist and what can we learn from such frameworks and methodologies.

Looking Back

Business decisions do not happen in isolation, and data was and is used to improve on the effectiveness of these decisions. Drawing the right conclusions from data finds the best way to achieve business goals. Before Big Data there was Data Mining, (before the Data Lake the Data Warehouse), and we are now in the third wave (summer) of AI. As new ideas/best practices do not arise in a vacuum, it helps to be knowledgeable about what came before and see how to move beyond it.

Data Mining

Let us start with Data Mining (DM). What is colloquially meant by DM is a process of knowledge discovery and extraction out of large collections of data. This sounds not far away from today’s Data Science and Engineering as the footing is the same: We have lots of data and we want to get insights and value out of it. Let’s explore how the application of DM looks like in practice and then compare current standards to it.

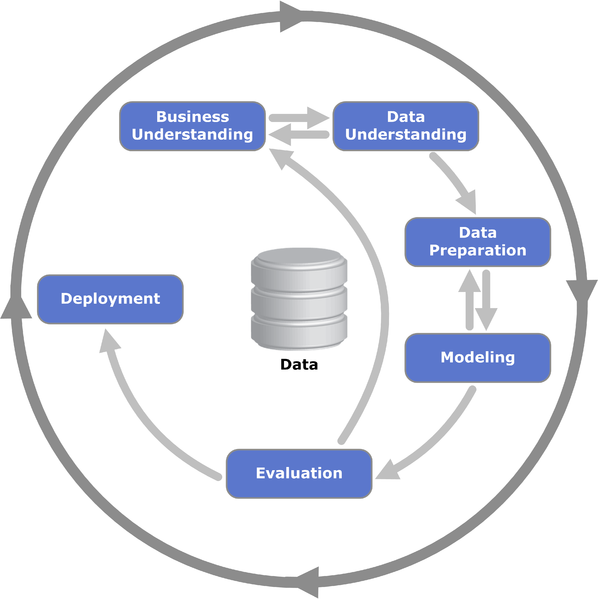

A widely used business standard for DM is the CRoss Industry Structured Process for Data Mining (CRISP-DM)1. It shows how data mining is applied in a productive business context and describes a data life-cycle to get from business requirements to delivering a usable data model.

As we will see with many similar processes, CRISP-DM represented by a cycle consisting of six interlinked steps:

- Business Understanding: Understand the question that is being asked and how it affects the business side, so that answering it can contribute something meaningful.

- Data Understanding: Get an overview of the available data and evaluate its usefulness for the task at hand.

- Data Preparation: Transform the data to a format suitable for the next steps.

- Modeling: From the transformed data derive models using statistical or analytical methods which are helpful in the business context.

- Evaluation: Do the models actually provide an answer to the initial question?

- Deployment: Put the models into production and available for business.

The cycle of CRISP-DM is described at a high level with no specification to e.g. data size, time frame or technical deployment. In its simplest form, CRISP-DM could be used to improve a single KPI like a churn rate for one product. Here, only data related to this product is relevant and used to derive or train a statistical model, which delivers predictions for the KPI. The resulting model of a CRISP-DM process doesn’t have to be a numerical model. The business question might be that inefficiencies in a business process need to be identified and resolved. Then, an action plan, e.g. for the restructuring of the process, is a valid model candidate of a CRISP-DM process and its implementation is part of the deployment phase. So we see that CRISP-DM can be applied at very different scales of a business to deliver actionable results.

Common feedback mechanisms are provided within CRISP-DM and the process is not linear but rather contains loops to react to new insights. This includes:

- A link between Business and Data Understanding. A clear understanding of the business case drives the data exploration, knowledge gained from exploration helps to refine the line of questioning required to extract value from possible results.

- A strong coupling between the Data preparation and Modeling steps. It is a common theme that after the initial data preparation a first model candidate can be chosen, which then leads to new parts in the preparation, e.g. engineering of certain features.

- On a broader scale, the Evaluation of a model candidate might lead to changes in the Business Understanding which affects all the steps in between.

Agile Influence on Data Science projects

Data projects, as emphasized by CRISP-DM, have never been linear but contain feedback loops, where the result of one step often requires us to go back to a previous one for further refinement. In parallel, such a process has been formalized in the context of modern project management. There, the usage of Agile methods, like SCRUM or Kanban, lead to short iteration periods and team-focused interactions to achieve rapid release of usable products. In (our sister-discipline) software engineering, the application of these methods gave rise to several concepts which focus on ensuring high code and testing quality in these short development cycles. Here, Continuous Integration (CI) and Continuous Delivery (CD) as well as Continuous Deployment stand out as advanced standard practices.

- With CI, we put our code under version control and push it regularly to a common remote repository where artifacts are built and tested automatically with each push. This circumvents possible issues when trying to integrate code changes in the productive environment.

- When CD is used in a project not only are artifacts built but also deployed in so-called test and staging environments where the product can be thoroughly tested in close-to-productive environments before releasing it to the actual production environment.

- An extension of Continuous Delivery is Continuous Deployment, where changes are automatically integrated and tested through all stages and put into production when no errors arise.

Status today

Ok, so people realized in the past that it helps to look at structures and processes when working with data, instead of only focusing on how to optimize model accuracy. But how did these processes evolve for modern Data Science? To answer this question we will look at a few models (hey, this word can also mean “general process description”, not only “neural network architecture”) that have been proposed in recent years.

CRISP-ML(Q)

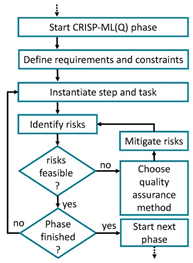

In 2019, experiences around the Mercedes-Benz AG Research culminated in a proposed CRoss-Industry Standard Process model for the development of Machine Learning applications with Quality assurance methodology CRISP-ML(Q) - catchy!

The authors saw the need for industrial organizations to have reliable standards in place for process handling and quality assurance in ML projects. This process model uses mostly the same key steps as CRISP-DM, with the following changes:

- Business and Data understanding are combined into a single phase, emphasizing the strong link between the business requirements and the available data at hand which is already noted in the original.

- Monitoring & Maintenance is added as an additional step at the end and consists of all the ongoing work after the first deployment of a model into production, i.e. monitoring model performance to account for distribution shift and using new data for re-training the model.

- Quality assurance is emphasized for every step of the project: for every step the stakeholder should define requirements and constraints, identify risks, and follow a defined workflow to decide if those are feasible, can be mitigated or if the step has to be reiterated completely.

While those steps and the quality gates are still formulated in a “waterfall” like process, the authors emphasize that this is always an iterative process and individual steps or sequences of steps will have to be repeated based on later results.

CRISP-ML(Q)2 introduces a focus on Quality Assurance and hints that the work with modern Data Science models is not over as soon as they are deployed, but otherwise it is not a big jump from CRISP-DM.

TDSP

Microsoft presented the Team Data Science Process in 2016. It is strongly based on CRISP-DM, and the project lifecycle is defined in the major phases Business Understanding → Data Acquisition and Understanding → Modeling → Deployment → Customer Acceptance, where each of the phases can be iterated when required. A perspective unique to TDSP is that work in a DS project is structured around the different roles present in a team (e.g. Project Lead, Data Scientist, Solutions Architect, …) and a clear distribution of tasks and responsibilities.

So there is no big surprise in TDSP. Let’s maybe look at a few different perspectives, that have caught quite a lot of traction in the community:

MLOps

In 2014 Google began publishing their experience that they saw ML Systems quickly becoming overwhelmed by technical debt: the large amount of code necessary for everything that is not actually the ML model (like data handling, resource management, automation and much more) required more and more effort and could quickly slow down to halt the innovation on the actual ML part. MLOps was proposed as a way to tackle those problems, automating more and more necessary steps in the process, akin to tried and tested DevOps practices.

They measure the MLOps maturity of a project in three general phases: MLOps level 0, 1 or 2 measure the amount of automatization to push data transformations, model training and a final model to production. This range starts at a completely manual process based on scripts and notebooks, with rare (and technically complicated) deployments of models for predictions (level 0). The goal is to first automate the pipeline for model training and deployment (level 1), and then to automate the process to change and experiment with this pipeline (level 2).

MLOps is less of a process model and more an outline for what should be the technical goal of a Data Science Project in an enterprise setting. And while this perspective is tailored to huge, highly volatile systems (think “Google”) and can often be challenged in detail for smaller projects, it has still resonated massively with data professionals everywhere. Nowadays there are growing more and more other perspectives on this topic, with many different providers offering technical solutions for specific parts of this problem.

CD4ML

Thoughtworks started to frame Data Science engineering practices under the term CD4ML around 2017, and the concept behind those is so valuable, there is already an in-depth description of CD4ML on this blog.

The primary insight is that applying the tried-and-true CI/CD approaches to ML problems unlocks large additional values. When the relevant integrations are in place, ML projects take advantage of the safe (because small and tested) increments and frequent feedback through frequent releases which made CI/CD so powerful in the first place. The reason that it is not obvious to put those integrations in place is that CD4ML comes with quite some challenges compared to traditional software development:

- Data Science Teams are usually much more cross-functional than classical software dev teams, so CD4ML practices need to align the different perspectives / tools / workflows.

- A functioning CD process requires that all of Code, Models, and Data are in some form version controlled, since changes in each of those components can change the outcome of the final service (and therefore should trigger the CD pipeline).

CD4ML highlights the actual work that needs to be done, and describes detailed practices on how to develop in a Data Science Project. It sees itself as a “software engineering approach” but still you will find it covering the important steps to go from a business requirement to a valuable data product.

And to go from this very local perspective to a much larger one, let’s include ModelOps as well.

ModelOps

The community is still in the process of aligning on a single description of ModelOps, a term that stems out of IBM research in 2018, but it mostly centers around technical management of the models coming out of Data Science projects. ModelOps is framed as the capability of big companies to govern the many different models (not only ML) that are used and manage their life cycle. Therefore features like CI/CD integration (or basically the full MLOps processes) are an important part, but the main focus is on managing the operational models with monitoring, A/B testing, re-training, deployment and rollbacks from a central perspective.

While ModelOps is concerned mostly with practices and capabilities of higher management in large enterprises, it is based on the realization of ModelOps (and a clean handling of the different steps each data product or model has to go through) for every single project that is executed.

What do we learn from that?

This overview of abstract process models might seem like falling back into habits from the ivory tower of research (ok, you got me there) but from our perspective there are two really interesting points emerging:

A well-trained model on its own is worthless

All those people who looked at how to generate value with their Data Science projects came to the result, that training a model is only a tiny part of a successful project. There are always many steps before and after this part, and to lead to success these steps must be considered from the beginning. Especially for a Data Scientist, it is often too tempting to focus just on getting these additional 1.8% accuracy, and while such a feat would push you to the top of the kaggle board in a competition, in a professional context our time is much, much better invested working on the many other parts of a successful project.

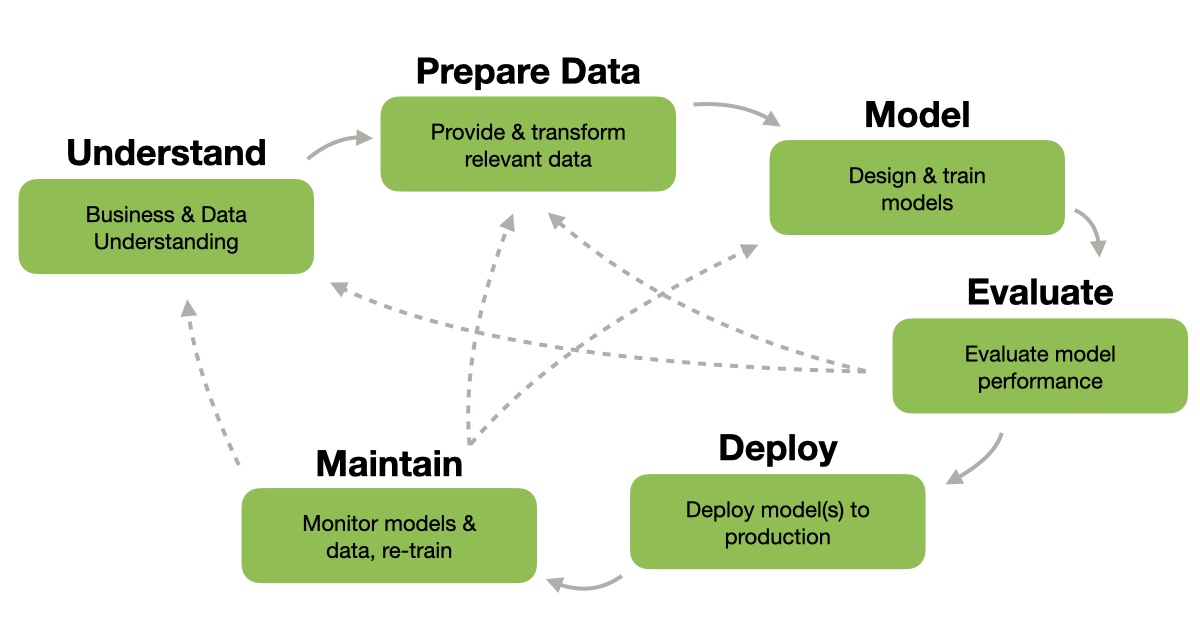

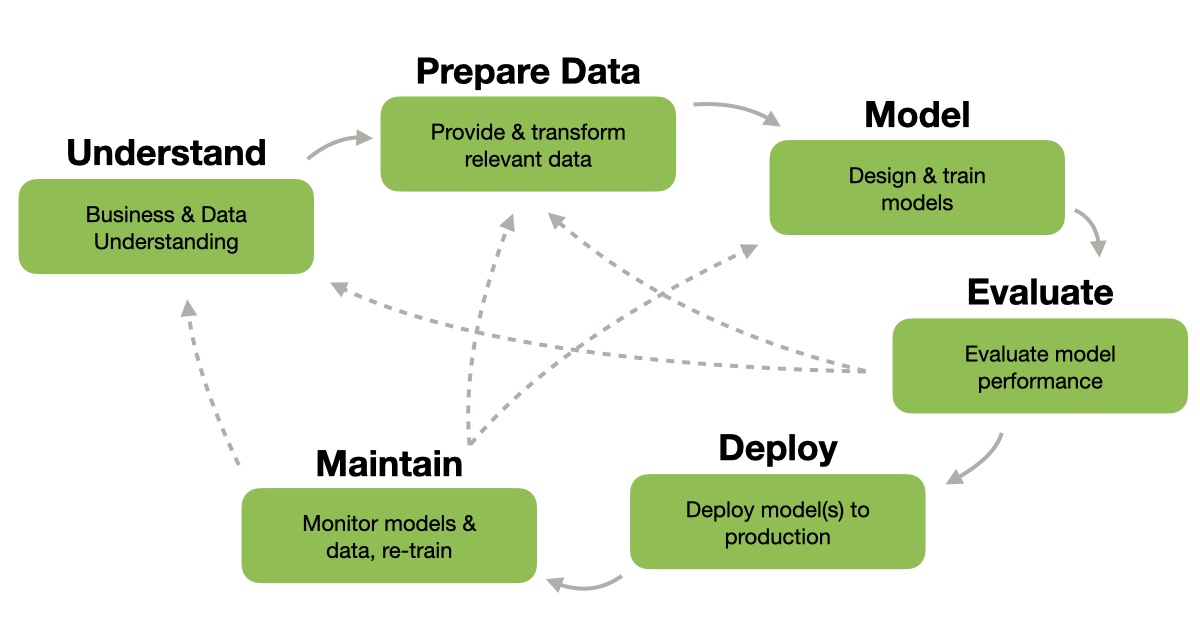

Data Science projects run in common phases

We have looked at a range of different views on Data Science projects, with perspectives on the work of an individual Data Scientist, the management of data driven projects by a CIO or anything in between. All those different views largely agree on a handful of steps that an individual Machine Learning project almost always goes through. For our internal perspective, we created our own figure summarizing those steps (because the million existing figures of this content that are already out there were not enough). And of course, different projects will maybe cover only a part of this process or go through multiple iterations. But when talking about different projects or considering how to improve on our current task we find it extremely helpful to abstract back to this perspective and think where we are on the circle and what we want to achieve in the next steps.

Finally

For us, having an overview of these models really helps to make it clear where in a project we are at the moment, and which steps are connected to our tasks both up- and downstream. Producing value for a business project is only possible when all the required steps in the cycle work well together. That makes it easier to realize when it might be best to switch from working on model training to e.g. reconsider the data we use in the project. And it allows us to keep the connected tasks in mind when we decide on tools and architectures.

What does it mean for Jupyter? There are companies that use dominantly notebooks for Data Science projects in production (e.g. Netflix has an elaborate setup). But the Data tool landscape is much larger and for each task and situation there are plenty of tools to choose from. This poses the question: how to make this choice, and what is the best fit?. More on this coming up next.

image for CRISP-DM from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CRISP-DM_Process_Diagram.png ↩︎

image for the QA workflow from https://www.mdpi.com/2504-4990/3/2/20 ↩︎